Mulholland Drive (2001)

David Lynch's "Mulholland Drive" is an enigmatic masterpiece. A film that resists interpretation yet begs to be understood, one that operates as both an emotional gut punch and an intellectual puzzle. As a filmmaker inspired by Lynch's artistry, I consider "Mulholland Drive" his most brilliant, cohesive work… a culmination of the themes, stylistic flourishes, and philosophical ideas that defined his career. It distills his fascination with identity, dreams, and the subconscious, his conflicted relationship with Hollywood, and his lifelong engagement with transcendental meditation into a singular vision.

In light of Lynch's recent death, the film feels even more significant, especially when considering how his art often grappled with death, not just as an end but as a transformation. While "Mulholland Drive" isn't explicitly about death, it exists in a liminal space where endings and beginnings blur. Like so much of Lynch's work, it's haunted by a sense of impermanence, of lives unraveling and reforming, of identity dissolving into something greater or darker. Watching this film now, it's impossible not to feel the weight of his absence and the way his art continues to speak to the mysteries of existence.

"Mulholland Drive" serves as Lynch's most profound exploration of Hollywood, and it is through this lens that much of the film's meaning unfolds. He has always viewed Hollywood as a paradox, a place where dreams are born and simultaneously annihilated. His reverence for its magic clashes violently with his disgust for its systemic cruelty, and nowhere is his opinion clearer than in this film.

The grotesque figure of the "The Bum" represents the dark underbelly of Hollywood. Emerging from the shadows behind Winkie's diner, this hideous figure embodies the industry's ugliness, the invisible machinery that chews up dreamers and spits them out. The vagrant is not just frightening but deeply symbolic: a grotesque manifestation of the despair and destruction hiding beneath Hollywood's glittering facade. In many ways, it feels like a stand-in for Diane, whose journey from wide-eyed optimism to shattered despair parallels the corrosive effects of Hollywood's promises.

I've personally encountered both the allure and darker realities of this industry, and find this metaphor deeply resonant. It is a reminder of the cost of pursuing dreams in a system that thrives on commodifying human potential while discarding those deemed unworthy. It is Lynch's way of pointing to the unspoken casualties of Hollywood's relentless appetite for success, and it is terrifying in its honesty.

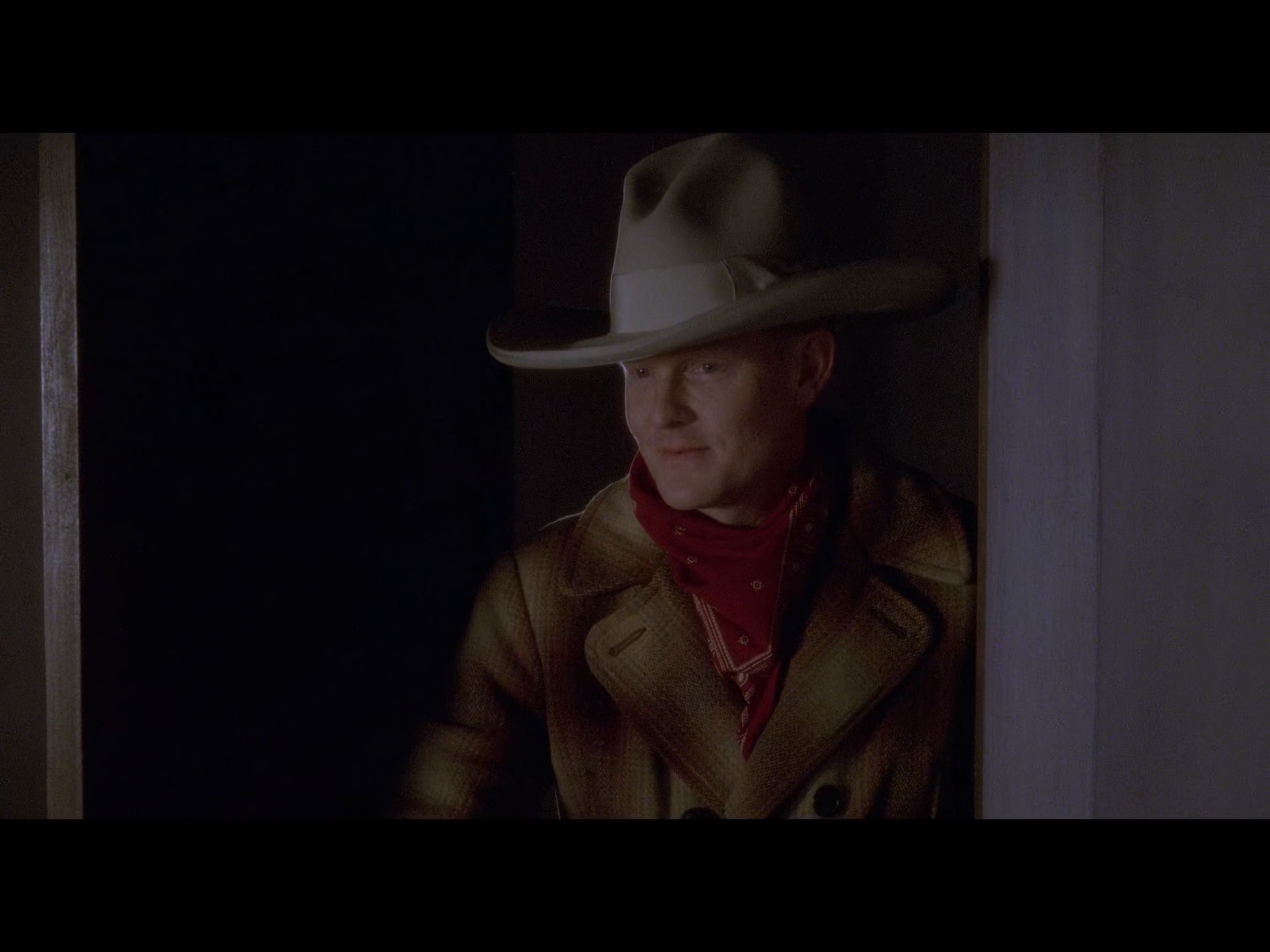

The Cowboy is another mysterious figure in "Mulholland Drive," but to me, he symbolizes Hollywood's cold, omnipotent forces. With his calm, unremarkable demeanor and cryptic admonitions, the Cowboy seems like a godlike arbiter of fate, a reflection of the unseen powers that be who control destinies in the entertainment industry. When he tells Adam Kesher (Justin Theroux), "you’ll see me one more time if you do good, you’ll see me two more times if you do bad," it feels less like advice and more like a decree.

The Cowboy's presence underscores one of Lynch's key ideas: the lack of agency individuals have within the larger systems that govern their lives. In this case, that system is Hollywood, a world where decisions are made in shadowy corners, dictated by forces that are indifferent to personal ambition or morality. But there's also something universal about the Cowboy's role, something that transcends Hollywood. He acts like a karmic force, delicately balancing Lynch's fascination with fate and free will.

While many interpret “Mulholland Drive” as Betty being Diane's dream projection, the film offers more interesting possibilities, particularly when viewed through Lynch's recurring motif of doppelgängers. Throughout his work, especially in "Twin Peaks" with its doubles and doppelgängers (Laura/Maddy, Cooper/Mr. C), Lynch has explored the idea of parallel selves existing simultaneously. In this light, Betty and Diane could be understood not as dream/reality versions of the same person, but as cosmic doubles… mirror images whose fates are mysteriously intertwined.

Similarly, Rita and Camilla can be viewed as doppelgängers, each representing different possibilities of the same archetype. This interpretation adds layers to the film's exploration of identity, suggesting that rather than a simple dream/reality split, the film is depicting a more complex splintering of reality itself, where multiple versions of selves can coexist and influence each other.

This reading aligns with Lynch's broader metaphysical interests and his fascination with parallel realities. The film's structure, with its mysterious blue box and key, could represent portals between these parallel existences rather than simply transitions between dream and reality.

Lynch's exploration of fractured identities and merging personalities in "Mulholland Drive" bears remarkable similarities to Ingmar Bergman's groundbreaking film "Persona.” Like Bergman's film, which depicts the psychological merger between an actress and her nurse, "Mulholland Drive" presents us with women whose identities become increasingly fluid and interchangeable. Lynch has cited Bergman as an influence, and the parallel is particularly evident in both films' use of close-up shots that blend their female characters' faces, suggesting a merging of identities.

Both films also share a preoccupation with the nature of performance and authenticity in relation to identity. Just as Bergman's Elisabet Vogler questions the authenticity of all human interaction through her voluntary muteness, Lynch's Betty/Diane and Rita/Camilla exist in a world where performance and reality become indistinguishable. The now famous audition scene in "Mulholland Drive," where Betty transforms from seemingly naive newcomer to commanding actress, echoes Bergman's exploration of the thin line between performed and authentic identity.

Moreover, both directors use the film medium itself to comment on the illusory nature of cinema and reality. Bergman's famous film strip burning and camera crew shots find their spiritual successor in Lynch's Club Silencio scenes, where both directors remind us that everything is an illusion. These meta-cinematic moments serve to destabilize our perception of what's real within the narrative while commenting on the nature of cinema itself.

Another fascinating aspect of Lynch's artistry is his connection to transcendental meditation, and this film feels deeply informed by his spiritual practice. Lynch has spoken openly about TM as a means of accessing what he calls "the unified field," a space of infinite creativity, beauty, and possibility. This philosophy is embedded in the structure and tone of “Mulholland Drive.”

Much of the film feels less like a conventional story and more like a meditative journey. The cyclical nature of the narrative, with different layers of reality, reflects Lynch's belief in the interconnectedness of all things. The mysterious Club Silencio, with its eerie proclamation that "everything is an illusion," encapsulates the film's metaphysical underpinnings. For Lynch, art and life are inseparable from the infinite, there is always something deeper, something beyond the surface.

But Lynch also recognized the duality of transcendence. Just as meditation allows for the expansion of consciousness, it also reveals the darkness buried within. Diane's descent into despair is the shadow side of this spiritual journey, a reminder that transcendence requires confronting the ugliness lurking beneath the surface.

Though Lynch rarely spoke about death in explicit terms, his films, including “Mulholland Drive,” hint at his understanding of it as both a fracture and a continuation. Death, like identity or time, is not linear in Lynch's world…it echoes, reverberates, and reshapes itself. Diane's fate may be tragic, but it is not final… the reality continues, looping back upon itself, suggesting that existence is as eternal as it is ungraspable.

For me, this is the ultimate gift of Lynch's art: the willingness to confront life's mysteries without attempting to resolve them. His films acknowledge the beauty and terror of existence and, in doing so, transcend the boundaries of film itself.

I've written about “Mulholland Drive” as a work of ideas, but its emotional core lies in Naomi Watts' stunning performance. She embodies both the hope and agony of Diane's journey, shifting seamlessly between personas that feel impossibly far apart yet deeply connected. In her hands, Betty's exuberance is as believable as Diane's anguish, and it is through her performance that the film's themes of identity, trauma, and failure hit with such devastating impact.

Watts' performance reminds me why actors are essential collaborators in the filmmaking process. She doesn't just serve Lynch's vision, she elevates and transforms it, grounding the film's surrealism in a raw, human truth. It’s truly awe inspiring to witness her command, her vulnerability, and her willingness to embrace the contradictions at the heart of “Mulholland Drive”feels timeless, a work that encapsulates his artistic and spiritual legacy. Watching it now, I'm reminded of why I became a filmmaker: to explore the uncharted territories of the human experience, to grapple with the profound mysteries of life and death, and to create something that lingers in the hearts and minds of those who encounter it.

Lynch has given us a masterpiece not because he provides any answers, but because he gives us permission to live inside the questions. And as someone who continues to be deeply inspired by his artistry, I can think of no greater legacy.