La Jetée (1963)

In my endeavor to study experimental film, both in school and beyond, Chris Marker’s “La Jetée” stands out as one of the most influential to my own work, and continues to inspire me. It’s a landmark in experimental cinema and science fiction for its innovative storytelling and profound exploration of memory, time, and human existence. This 28-minute French film, constructed almost entirely from still photographs, redefines cinematic language by embracing time and editing as its core tools of expression.

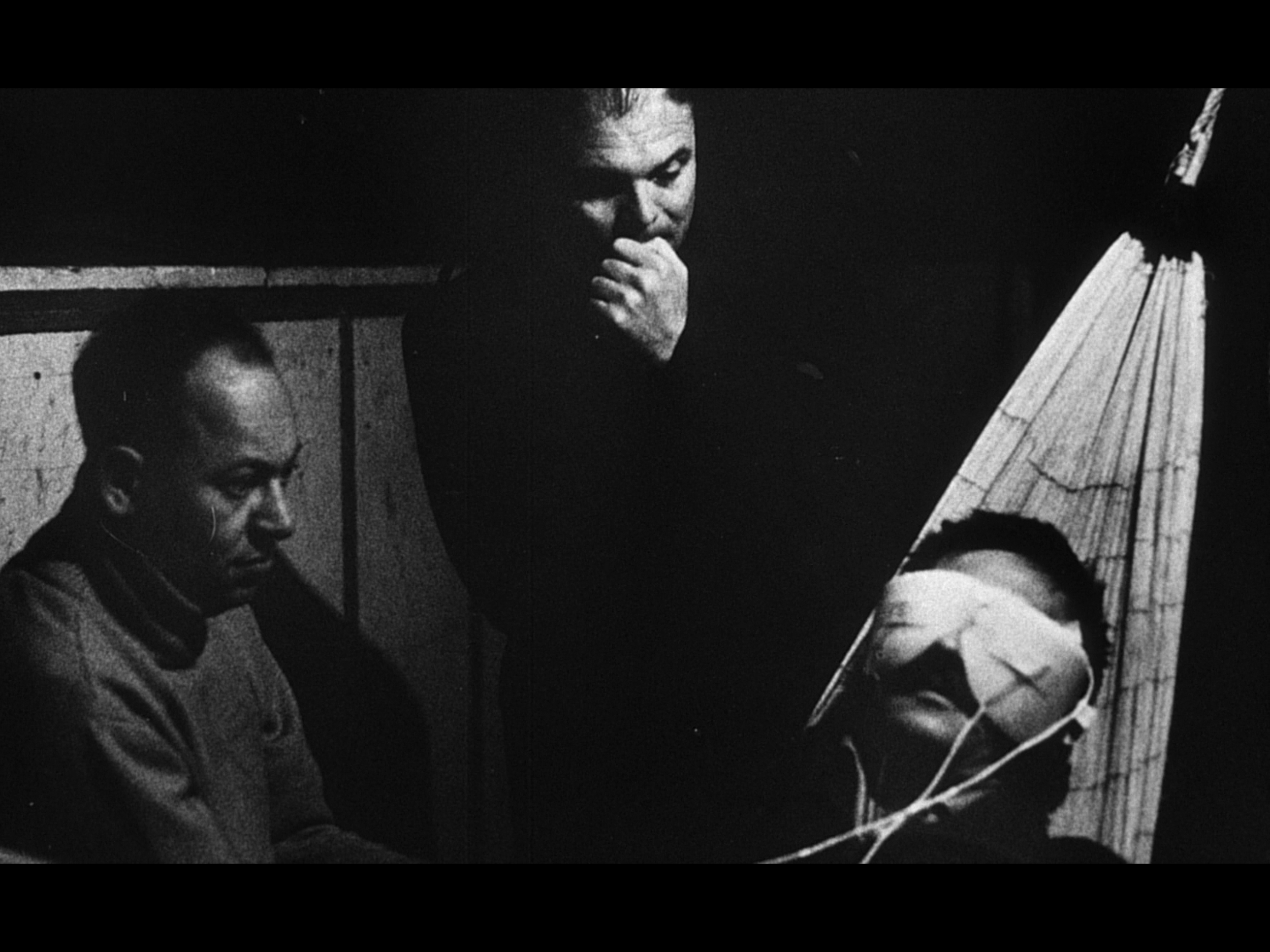

“La Jetée” examines the interplay between memory and time. The Man (Davos Hanich), haunted by a childhood memory of witnessing a man’s death at an airport, discovers through time travel that he is the man in his own memory. This revelation underscores the inevitability of fate and the cyclical nature of time. The film suggests that memory is both a tether to the past and a force that shapes our understanding of existence.

Set in a dystopian future after World War III, the film reflects Cold War anxieties about nuclear annihilation and humanity’s fragility. Its depiction of underground survivors conducting desperate experiments evokes themes of displacement, survival, and the psychological scars of war.

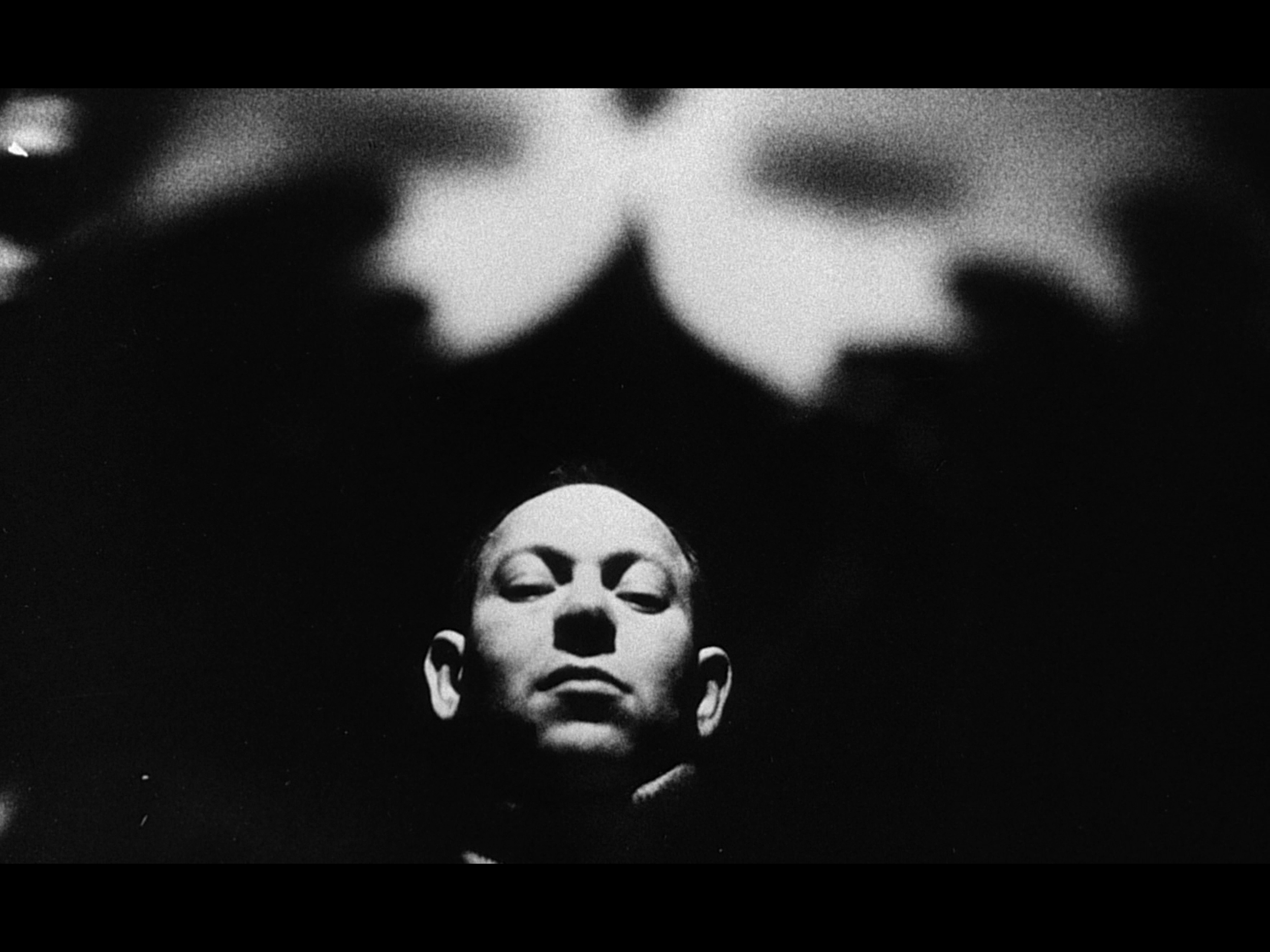

The film’s use of still photographs instead of moving images challenges traditional cinematic conventions. By relying on static frames combined with narration, sound effects, and music, Marker creates a sense of motion and continuity that feels dreamlike yet precise. This technique emphasizes cinema’s unique ability to manipulate time, freezing it within individual images while allowing editing to create rhythm and progression.

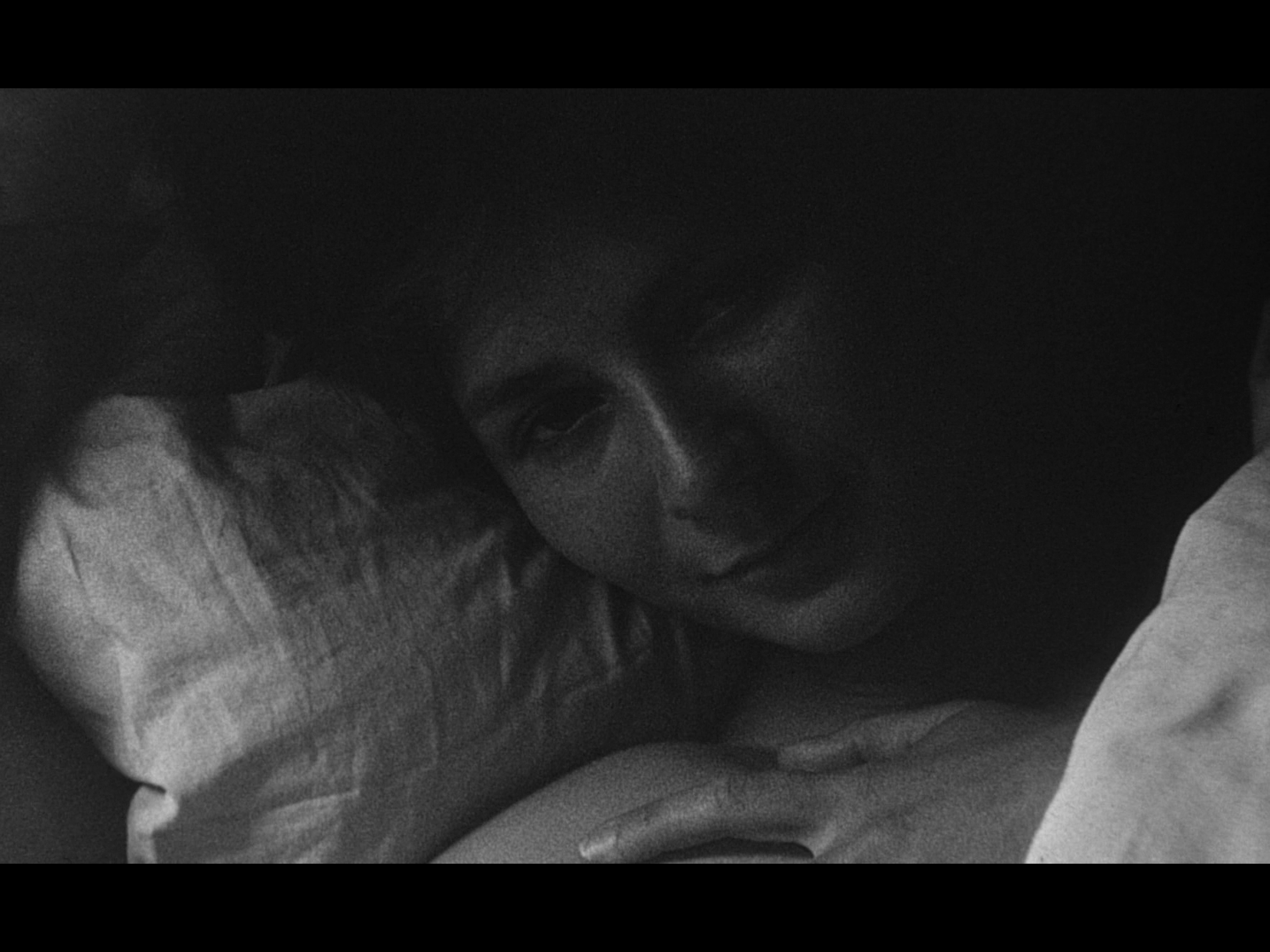

The stillness mirrors The Man’s fixation on specific moments in his life, reinforcing the themes of memory and temporal stasis. The single moment of motion when The Woman opens her eyes becomes profoundly impactful within this context, symbolizing life amidst stillness.

Marker’s editing transforms static images into a dynamic narrative experience. Fades, dissolves, and rhythmic sequencing guide viewers through temporal shifts while evoking emotional resonance. Editing becomes not just a technical tool but the very language through which “La Jetée” communicates its ideas about time’s fluidity.

The sparse yet evocative soundtrack enhances the film’s atmosphere. Narration provides structure, while sound effects like heartbeats and orchestral music heighten tension and emotion. Together with the editing, sound bridges the gaps between still images, creating an immersive cinematic experience.

Chris Marker’s decision to use still frames was deeply deliberate, reflecting his philosophical exploration of time, movement, and cinema itself. The still images serve as a meditation on the nature of memory and the passage of time, emphasizing that life is experienced as fragmented moments rather than continuous flow. By constructing the film as a "photo-roman,” Marker draws attention to cinema's fundamental illusion: motion created from stillness. This approach forces viewers to confront how editing creates meaning by simulating time’s progression.

As part of France’s Left Bank artistic movement, Marker drew from avant-garde traditions that blurred boundaries between photography, cinema, and literature. This intellectual context shaped the film’s experimental approach and philosophical depth.

“La Jetée” has left a significant mark on cinema. Terry Gilliam's “12 Monkeys” expanded the narrative into a feature film while retaining its central themes. Its influence can also be seen in other works that explore time travel or experiment with unconventional storytelling.

Chris Marker’s “La Jetée” is a profound meditation on time, memory, love, and loss that reimagines cinematic language itself. By embracing stillness while using editing as its primary mode of storytelling, it highlights cinema’s unique ability to manipulate time—both visually and emotionally. Its innovative form continues to inspire filmmakers worldwide while reminding us that we are all bound by the inevitable flow of time.