Le Samouraï (1967)

Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Le Samouraï” opens with a quiet promise: the definition of a samurai flashes on the screen, setting the stage for a film that won’t just tell us a story but draws us into the pathos and discipline of a warrior bound by his own code. Though set in contemporary Paris, Melville’s austere masterpiece is steeped in the timeless ethos of bushido, embodied in Alain Delon’s Jef Costello, a hitman who moves through the shadows of a cold, indifferent world like a predator honoring a creed written only in his own mind.

Melville wastes no time establishing the tone or narrative rhythm of his film. Within the first ten minutes, we’ve been introduced to Jef’s detached efficiency: he steals a car, takes it to a fixer to swap the plates, and acquires a gun—all without uttering a single word of dialogue. Melville is a maestro of visual storytelling, and here he conducts a symphony of movement, expression, and silence. Dialogue is spare throughout, and yet the film speaks volumes. It whispers in the hushed tension of its muted colors and sighs through the deliberate, slow pace of its cuts. We never miss the words.

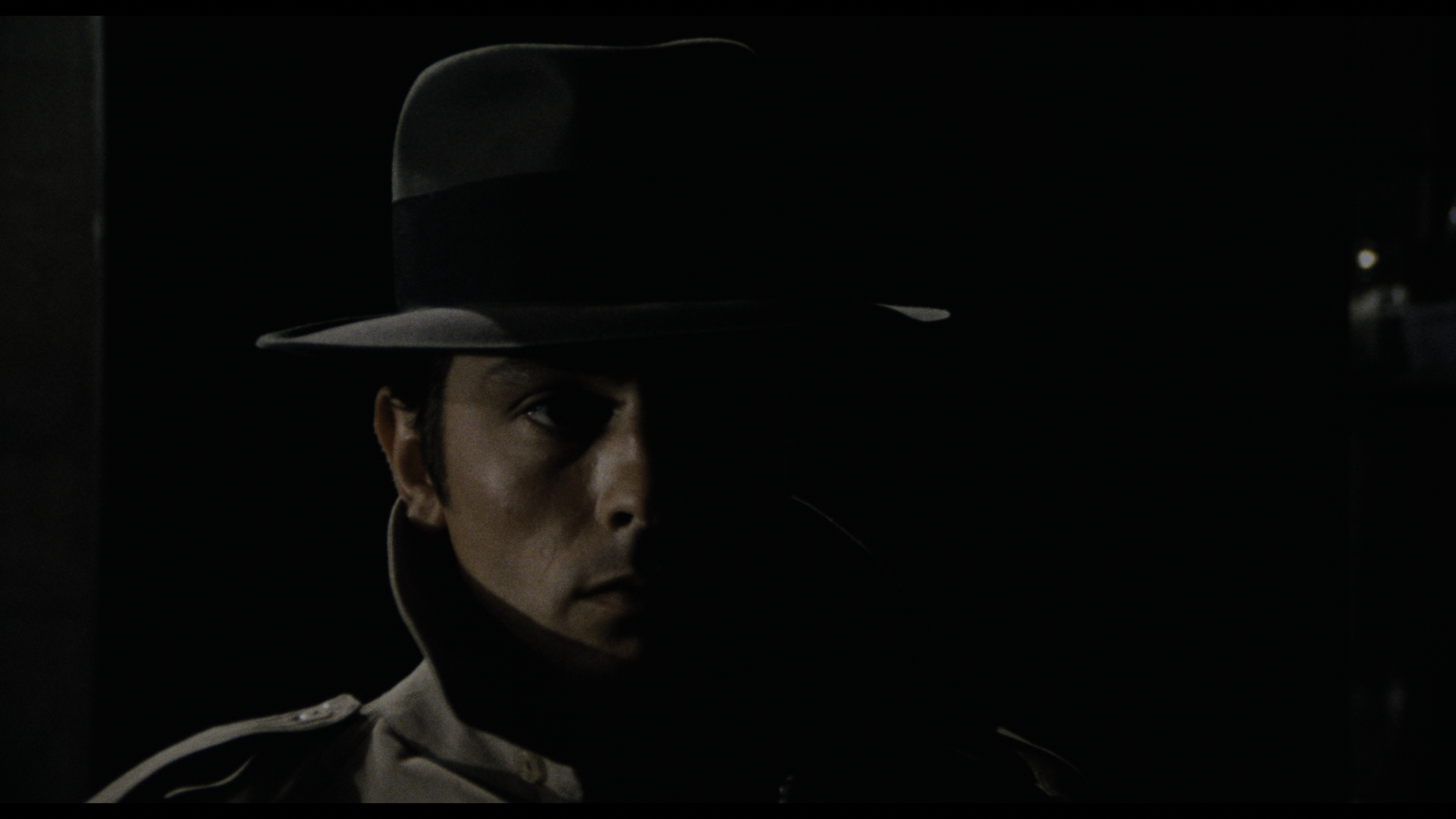

Visually, this film is an ode to noir traditions, updated for a colder, more existential era. The cinematography, awash in shades of blue, gray, and dark shadow, creates an atmosphere of detachment and alienation. Night scenes are particularly striking, with just enough light and detail to guide us through the grimy streets and smoky nightclubs of a Paris that feels as much a character as Jef himself. Melville’s choice to shoot on location enhances the film’s raw, tactile realism. Paris is not romanticized here. Instead, it becomes a labyrinth of both beauty and menace, a stage for an elegant yet ruthless game of cat-and-mouse.

Jef Costello is a man who exists beyond words, and Delon’s performance is a perfect match for this enigmatic role. With his stoic demeanor, icy blue gaze, and impeccable trench coat, Delon doesn’t just play Jef Costello, he embodies him. His every gesture is deliberate, from the way he lights his cigarette to the precise way he dons his fedora. Delon’s minimalist approach amplifies the sense that Jef is a man bound by a moral code he cannot articulate, a man who has shaped his life into a ritual of efficiency and solitude but whose carefully constructed world is beginning to crumble.

Melville carved out a unique niche in French cinema, blending the existentialism of post-war Europe with the fatalistic romanticism of American film noir. “Le Samouraï” is perhaps the pinnacle of this synthesis, and it reflects Melville's fascination with the codes of honor, loyalty, and solitude that govern both the samurai and the criminal underground. To watch this film in the larger context of Melville’s work, such as “Bob le Flambeur” and “Le Cercle Rouge,” is to see a filmmaker refining his craft, stripping away excess and ornamentation until only the essence remains.

The film’s influence cannot be overstated. Generations of filmmakers have drawn inspiration from Melville’s detached antiheroes and precise visual style. Michael Mann’s “Heat” comes to mind, particularly in the way it pits intelligent criminals against equally methodical law enforcement. Like Jef Costello, Mann’s characters are professionals in their fields, bound by rules of conduct that isolate them from the world around them. Quentin Tarantino, John Woo, and Jim Jarmusch have all cited Melville as an influence, the latter paying his own homage to the samurai ethos with “Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai.”

What sets “Le Samouraï” apart, even decades later, is how masterfully it balances stillness and action, intimacy and detachment. It’s a film that trusts its audience, allowing us to step into Jef’s world and interpret it for ourselves. As the final, haunting shots unfold, we are left with a profound sense of quiet inevitability—a testament to Melville’s ability to turn even the act of dying into a moment of transcendent grace.

“Le Samouraï” isn’t just a crime thriller, it’s an existential meditation on solitude, identity, and the rituals that define our lives. Melville may have begun with a definition of the samurai, but the film itself is the real lesson: an exploration of what it means to live and die by one’s own code, even in a world that refuses to understand it.