Brazil (1985)

Terry Gilliam's "Brazil" is a surreal hallucination that attacks you with a deliberate visual force. Here is a rare creation where a director’s imagination is utterly unconstrained, yet paradoxically focused on creating a world that traps its inhabitants in endless corridors of bureaucracy and ductwork.

From the opening moments, Gilliam employs wide-angle lenses to create extreme distortions that mirror the warped reality of his world. We're thrust into a society where perception itself cannot be trusted. The visual language speaks volumes with Orwellian propaganda posters declaring "Loose talk is noose talk" and "Suspicion breeds confidence.” These slogans pervert positive human values into instruments of control. When characters pass walls bearing the message "Don't suspect a friend, report him," we witness the death of human connection itself.

The film's inciting incident is a marvel of chaotic causality. A dead bug falls into a printing machine, causing a clerical error that sets the entire plot in motion. This "bug ex machina" is Gilliam's wry commentary on how massive bureaucratic systems can collapse from the tiniest disruption. In a world obsessed with order, chaos remains the true ruler.

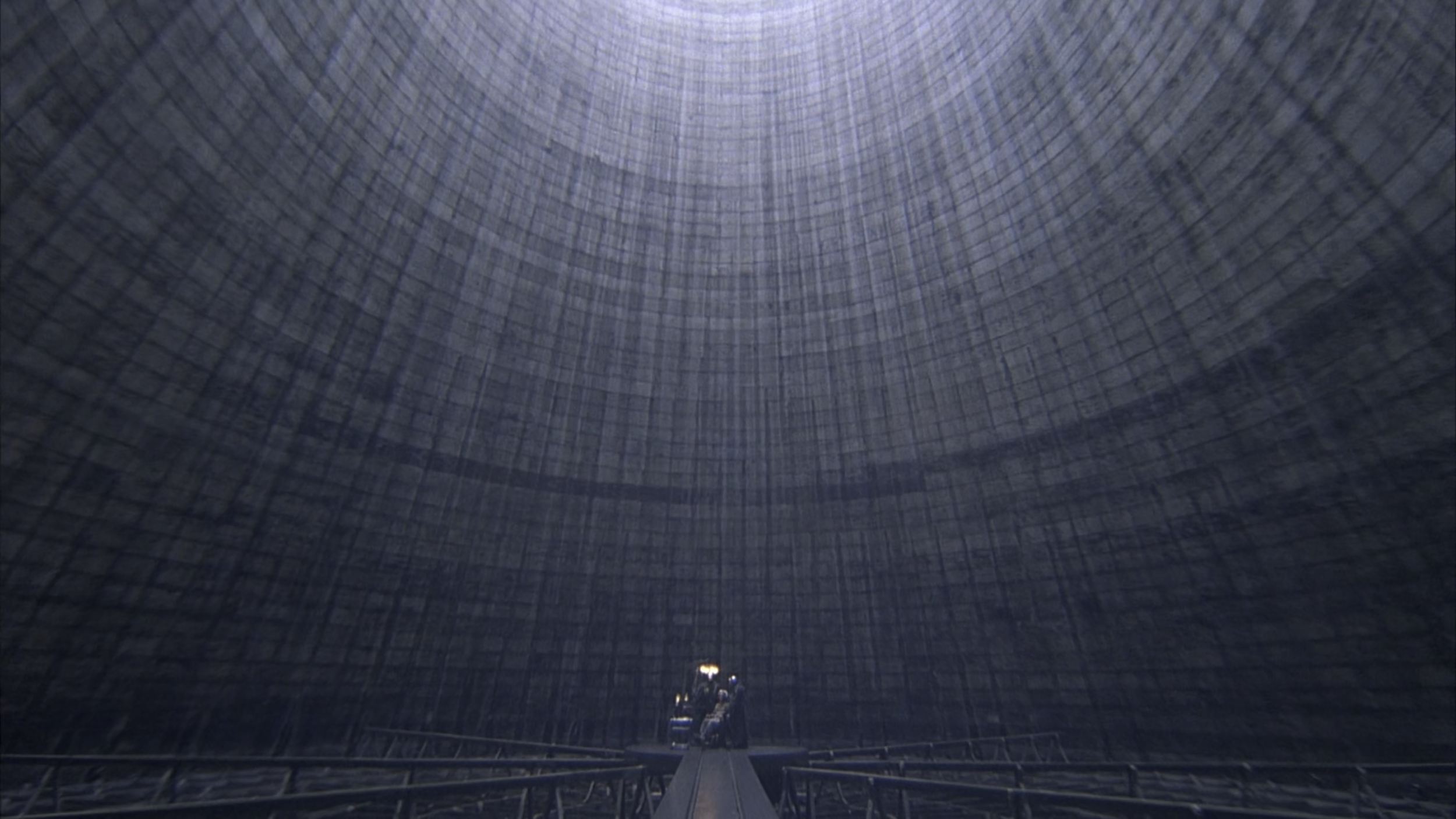

The omnipresent ductwork in "Brazil" is perhaps the film's most striking visual motif. These serpentine tubes snake through every space, choking buildings, homes, and lives. They serve multiple metaphorical purposes. On a practical level, they suggest a society dependent on artificial systems to survive, unable to breathe natural air in an environment they've corrupted. More profoundly, they represent the visible circulatory system of bureaucracy itself. The endless paperwork, procedures, and regulations that have become so complex they must physically manifest.

When rogue heating engineer Harry Tuttle (Robert De Niro) arrives to fix Sam's (Jonathan Price) air conditioning without proper paperwork, he's committing an act of rebellion against this system. "We're all in this together," Tuttle says, while Central Services official repairmen are ridiculously inefficient and destructive. The ducts function simultaneously as lifelines and chains, necessary for survival yet instruments of control and surveillance.

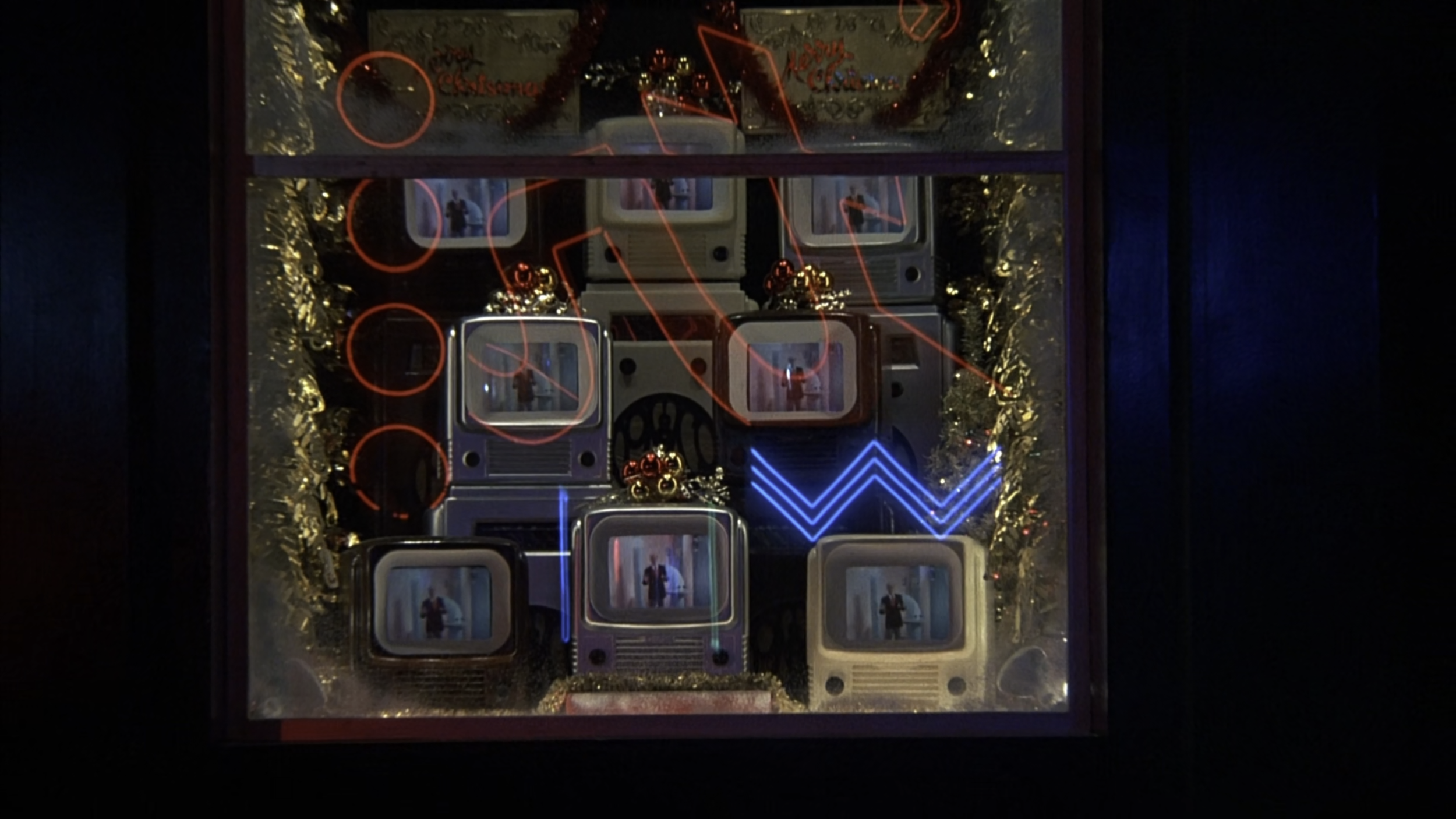

The genius of this film lies in how its production design feels both fantastically surreal and disturbingly plausible. The retrofuturistic technology with tiny screens attached to enormous fresnel lenses, pneumatic tubes carrying information, typewriters grafted to computer terminals, creates a world that never existed but somehow feels authentic. Gilliam's future isn't sleek and minimalist but cluttered, dysfunctional, and patched together from mismatched parts, much like the bureaucracy it represents.

This visual approach is complemented by Michael Kamen's classical score, which repurposes Ary Barroso's "Aquarela do Brasil" as a dreamlike motif. The music's grand, romantic quality contrasts ironically with the cramped, mechanical world onscreen, embodying Sam's inner yearnings for escape and beauty.

When Harry Tuttle is consumed by a whirlwind of paper, vanishing into the very bureaucracy he fought against, it's one of the most potent visual metaphors. This system doesn't just defeat its enemies, it absorbs them, transforms them into more of its endless documentation. It's a fate worse than death: becoming just another form, another statistic, another piece of processed information.

The resemblance between Sam's love interest Jill and his youth-obsessed mother suggests his confused relationship with women and authority, seeking in romance both maternal comfort and rebellion against the system his mother embraces. It's a Freudian nightmare played with dark comedy.

The film's final act, where Sam appears to escape with Tuttle's help, finds love with Jill, and retreats to a pastoral idyll, is revealed to be a mental retreat. Still strapped in the torture chair under Jack Lint's ministrations, Sam has gone to the one place the system cannot follow… inside his own mind. The revelation is devastating precisely because we've invested in this escape, just as Sam has.

This ambiguity about reality versus dream permeates the entire film. How much of what we've seen is real? Where does Sam's fantasy life begin and end? By refusing clear answers, Gilliam forces us to question the nature of freedom itself. Is mental escape still escape? Is happiness real if it exists only in your mind?

While Michael Radford's "1984" (released a year earlier) faithfully adapted Orwell's novel, Gilliam's "Brazil" captures its essence more profoundly. Where Radford's film is appropriately bleak and literal, Gilliam recognizes that modern totalitarianism arrives in paperwork, incompetence, and banality. The system in "Brazil" isn't efficiently evil, it's chaotically, absurdly evil, populated not by calculating villains but by politicians, bureaucrats, and ordinary people just following procedure.

Sam Lowry isn't arrested for revolutionary activities but for excessive paperwork, for trying to correct the system's errors using the system's own methods. This is Gilliam's brilliant insight: totalitarianism doesn't need to be competent to be oppressive. It just needs to be pervasive.

Released during the height of the Reagan/Thatcher era, "Brazil" subverts the prevailing political narrative of its time. While conservative governments championed deregulation rhetorically, Gilliam saw the contradictions: increased surveillance, expanded defense apparatus, and corporate bureaucracies replacing governmental ones. The film targets not just communism (the traditional dystopian villain) but consumer capitalism itself.

The Christmas shopping scene, where bomb victims are stepped over so shopping can continue, eerily anticipates our modern "thoughts and prayers" responses to tragedy. Gilliam recognized how consumption becomes a form of control, keeping citizens distracted with products while their freedoms erode.

What elevates this film to masterpiece status is how its form mirrors its content. The film is itself a labyrinthine construction of tangents, details, and contradictions, a bureaucratic nightmare about bureaucratic nightmares. Yet beneath this chaos lies careful construction and profound purpose.

In an era of increasingly formulaic blockbusters, Gilliam delivered a defiantly personal vision that refuses easy categorization. It's a comedy that horrifies, a political film that's deeply personal, a future vision that comments incisively on its present.

The final image of Sam, smiling vacantly while humming "Brazil" as blood trickles down the torture chair, ranks among cinema's most disturbing endings. He's found freedom the only way possible in this world, by abandoning reality altogether. We're left to wonder which is the greater tragedy: the system that broke him or the dream world where he now resides. And more chillingly, we're left to examine our own forms of escape from the systems that constrain us.

In this daring, visually astounding, and philosophically rich film, Gilliam has created not just entertainment but a warning, a puzzle, and ultimately a mirror.